Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Above and Below (2015) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium [2.52] |

| BGG Rank | 359 [7.37] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Ryan Laukat |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Introduction

We liked Above and Below enough to give it three and a half stars in our review – a good game teetering precariously on the edge of genuine greatness. It would only take a comparatively small push to send it into the abyss of being amazing. Wow, those are some mixed messages coming across in those metaphors, but what can I do about it? Nothing, that’s what.

‘You could rewrite the intr…’

NOTHING. THAT’S WHAT.

Anyway we’ve already done our duty with regards to the game itself, now it’s time to move into the comparatively structured territory of our accessibility teardown. Let’s see if we’re going to go above or below the site average.

Haha, I’m so funny. I have to keep saying that otherwise people I’m worried people won’t actually be able to tell.

Let’s get started.

Colour Blindness

Above and Below is a lovely looking game, and while colour blindness has an impact on that it’s not the case it’s going to be an impediment to play.

Colour isn’t used as the sole channel of information anywhere in the game, and despite it having a lot of different cards it has a relatively small number of different kinds of components. There are the villagers, which are marked by unique art and icons along the top that make no key use of colour:

Goods tokens all have their own art on them. While a few of these might be a little difficult to make out at a distance it’s rare that you genuinely need to worry about it in a context where you couldn’t easily query of other players with no leaked gameplay intention.

For example, players can put goods up for sale and it might not be immediately obvious whether rope, or ore, or paper is up for sale. However, asking what it is doesn’t risk anyone being able to change anything that matters in the game or in their own plans for play. Likewise close inspection is not going to tell anyone anything useful.

The individual cards have two different colour schemes for above and below, but again they also come with unique and identifiable art. The above cards have skies and soil and the below cards have cave roofs and cave floors. All the key information for play is located along the top and bottom of the cards.

We strongly recommend Above and Below in this category.

Visual Accessibility

There’s an awful lot of which a player needs to keep track in Above and Beyond. At the start of the game there will be a player board, six star cards, four key cards, four ‘above’ buildings, four ‘below’ buildings, and a central reputation board. That latter will contain five villagers that can be hired, the turn tracker, and the reputation trackers. I don’t even have a photo of that because there was too much to actually fit cleanly into the camera lens so I’m going to show you an extract from the manual which shows the ‘ideal scenario’.

The cards are full sized and reasonably well contrasted but they often contain multiple icons used in different ways with sizes conveying information.

For example, consider the 14 card in the top row in the photo above. The two there means ‘two victory points’ but the smaller two means ‘Two points per villager’. You see a similar thing in the other star cards – the difference in size isn’t large enough to be an obvious differentiator and the slash isn’t the easiest thing in the world to see at a distance. However, this is usually consistently handled in that the first victory point total will be the base amount and the rest is conditional.

However, if you look at the second row there are numerous small icons that are used to convey important information – the difference between a plus, an arrow, a curved arrow and a hand will likely be difficult to make out without close inspection and sometimes these are very meaningful distinctions. The hand means ‘Gain this immediately’ and the plus means ‘This is a recurring bonus you get at the end of each round’. As you might imagine, there’s a massive differential in game impact between these.

The building cards that are available for purchase also make use of problematic notation – the difference between dots around a good and an arrow is the difference between a fixed resource of a certain amount and a resource that regenerated every turn. The iconography isn’t unnecessarily complicated but it is not very visually accessible. I would certainly anticipate it being a problem that would require support from the table to deal with. Requesting some of that support is likely to yield gameplay intention too.

There’s some tactility in the game but in an odd way – it can actually be misleading. The way that goods on buildings work is that fixed resources get their quota of the good placed on them when the card is purchased, and others get replenished at the end of the round. While you can certainly tell the difference between a fixed quota building with two goods in a stack, it’s not possible to tell the difference between a recurring good and a fixed quota where there’s only one item left to harvest. Likewise between a recurring good that has been harvested for this turn and a fixed good that will never again yield a harvest. Again, it will be necessary for many players to get support from the table to deal with this, particularly in circumstances of total blindness.

There’s another issue here with regards to the goods track – a player will easily be able to tell by touch how many of a good is in a slot, and with familiarity will be able to internalise the progression of value implied by that. All goods share the same disc token profile though and there’s no way to tell individual goods by touch. Some of them share a visual silhouette and this is likely to be an issue that requires close inspection to solve. That said, the goods once placed remain in place and acquire a value upon attainment that doesn’t change. As such as long as a player has a good memory they likely will be able to recall the main features such as ‘Mushrooms aren’t worth to me but I don’t have any gems’ and this will guide decision making.

Other tokens in the game have a distinctive tactile profile – cider tokens versus potions versus coins. The three different denominations of coins feel meaningfully different in size and while they’re not as distinctive with regards to the potions as I would like I suspect in most circumstances it would be possible to tell them apart. In any case, the denominations used in the game will permit for accessible physical currency to be substituted in more problematic scenarios.

Probably the largest inaccessibility in the game with regards to this section is one we discussed when we talked about Tales of the Arabian Nights. The story book is set up in such a way that the person reading a story should not be the one making the decision because covert information is presented to the narrator. The listener makes a choice on the basis of imperfect information – they don’t know the outcome or the actual rewards they will get. It’s actually less of a problem here than in Arabian Nights because that required three players to handle the narrative and Above and Below requires only two. However, if one of those players is visually impaired it means that a minimum of three players will be required to handle this portion of the game.

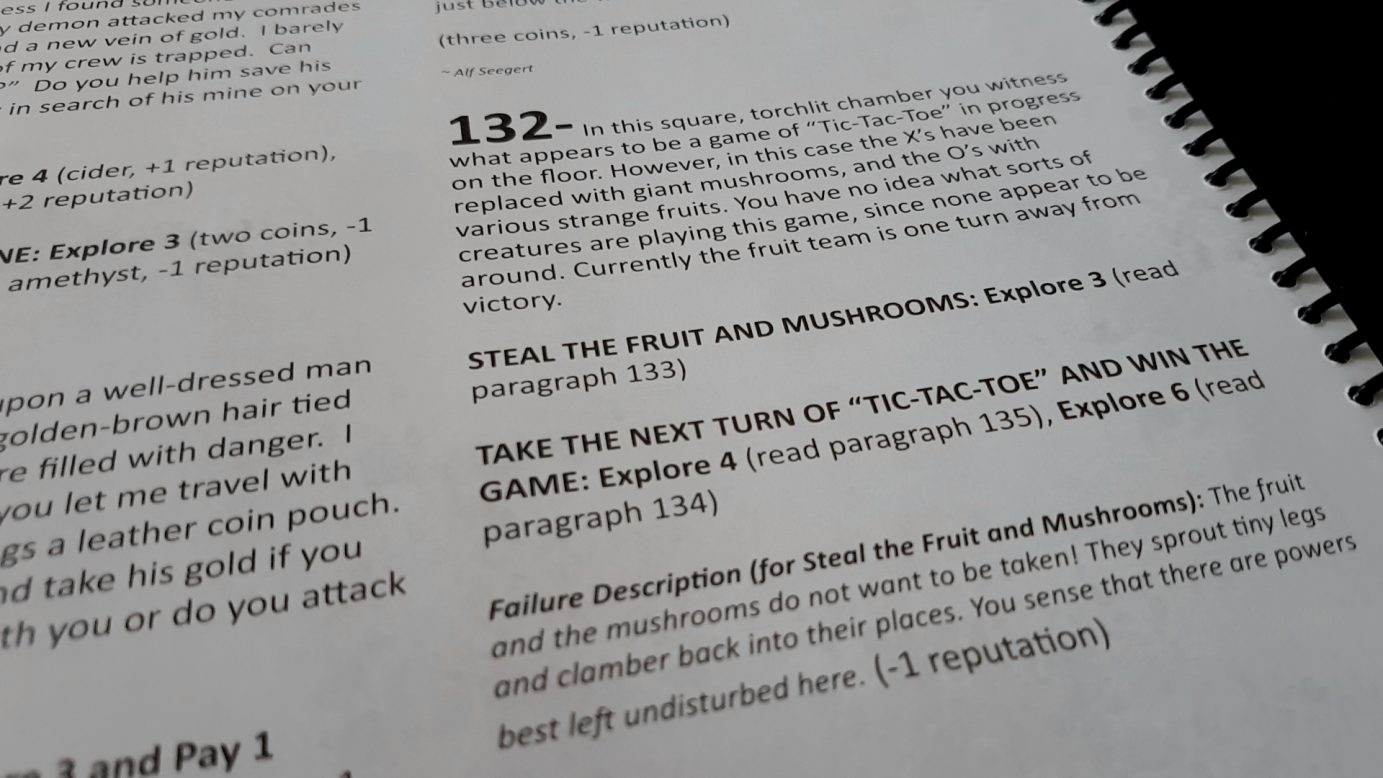

The text in the storybook is reasonably clear, well contrasted and in a readable font. Unfortunately sometimes the text is presented in italics (particularly for the rare passages where there are specific failure effects). It’s also small, and makes use of bold and unornamented text to convey important information with regards to what should be read and what shouldn’t. It’s also inconsistent in this respect – the main paragraph text (to be read aloud) is unornamented, and then when it comes to choices the part that isn’t to be read out is also unornamented where the choice itself is bolded. There’s also a fair amount of flipping through the book to find passages, although less so than in Tales of the Arabian Nights because there is much less story content here.

For the villagers, their capabilities are presented along the top of their individual ‘character sheets’, and while this is reasonably contrasted it’s also a surprisingly small amount of component real-estate to convey often dense information.

Consider the first villager to be shown here. The quill indicates that they can recruit new villagers, and if you roll a one on their adventure die you’ll get two successes and a five will get you three. In comparison though, look at some of the special villagers you might find as a result of encounters in the below:

The top left metal man has a lot of data – he has his own bed, his own success profile, but also potions and cider can’t be used on him. Those latter two icons are located in an inconsistent location but largely as a result of there simply not being any more room along the top. These icons are small, precise and important. The difference between getting three successes on a four and on a five is massive in the context of the game.

The final thing to be discussed here is that there’s a lot of dice rolling in Above and Below, but at least it uses standard d6s. You will need a number of these equal to the largest number of villagers you intend to put on a mission – at least, optimally. As long as someone makes a note of successes and there is a protocol for ‘exhausting’ villagers a single die could be substituted. Electronic dice rollers will also work fine.

We don’t recommend Above and Below in this category, but with a supportive table and a three-player count (where players don’t mind subbing in for a VI players when it comes to narration) it would likely be broadly playable.

Cognitive Accessibility

A lot of literacy is required to play Above and Beyond, at last as far as the storytelling element is concerned. As with the section on visual accessibility it would be necessary to have at least two literate players to properly play the game. The vocabulary employed in the story elements isn’t overly esoteric but it also doesn’t necessarily aim for plain English. The vocabulary employed is occasionally heavily influenced by the fantasy setting . The reading level is not excessive but it’s also not entirely straightforward.

There’s quite a lot of numeracy needed for play too – the value of goods is incremental, multiplicative, and not necessarily conceptually obvious from context. A gem might be worth dramatically less than an apple depending on how play has progressed – it all depends on where it is positioned in the goods tracker.

The victory points available to a player at the end is based on counting up the values on buildings, but also on some special effects if the right buildings have been purchased. Knowing the value of a building is based on a relatively complex calculation of immediate financial burden weighed up against when the value of the building will manifest and what opportunities a player will have to increase its value. One building for example provides two victory points for each villager, and that changes the relative value of every quill in the game, and that in turn puts a massive pressure on beds if a player is to get the most use out of them. On the other hand, if it’s the final couple of turns of the game you might just want to put everyone in ‘crunch mode’ and burn them out like you’re the management of Epic Games or Rockstar.

Game flow is reasonably consistent and predictable, although the exploration action has a tendency to derail any clear conception of flow of play. Exploration is a relatively complex, multi-part action that involves multiple die-rolls, narration, decision making and rewards. In comparison to more straightforward actions such as recruitment or building or harvesting it is a notably odd system of play. Other than that play rotates around the table until each player has passed after using up all the actions they wish to take, so it’s not as if anyone will forget what the play order is. It’s just that in terms of ‘How much of the game time is an action going to take up’, exploration takes by far the largest chunk of attention and complexity.

From a cognitive accessibility perspective, it’s important to assign the correct villagers to an expedition right up until the point it doesn’t matter. You want an optimal team in terms of what values they have for success in explore challenges, but weight of numbers will often suffice as a replacement for villager talent. As such, there’s a disproportionate burden of planning in earlier rounds – it’s important to recruit new people but that requires a plan to acquire the necessary beds or cider to keep them as functioning members of the society. Players that pay attention to the ‘critical path management’ of recruitment will begin to accrue advantage that acts as a kind of Matthew Effect, and buying a bed means that someone else won’t be able to get it. You need to be playing with all of these moving parts in mind, although as indicated at a certain point it stops mattering. With regards to decisions taken during the exploration phase, it’s rare that these are especially impactful other than with regards to the success values associated with rolls. You don’t know what you’ll get from a passage so you may as well just go with the response that’s most likely to be successful.

Game state is somewhat complex, particularly with regards to the creation and harvesting of goods. Not every harvest action is going to be equally useful, and not every good is going to be equally valuable. You want to acquire as many different goods as possible and if you can arrange it so that the most common goods are the ones you encounter the latest. A useful strategy for effective play is to make that which is common valuable, and that’s not something you get to do much in most games. There’s luck that come in to this, but there’s also an extent to which you can skew the odds through player trades and exploration.

Scoring then is numerically and strategically complex, with tactical considerations that must be taken into account with regards to the availability of key building resources. It’s asking a lot of players in this category.

For those with memory impairments only, there’s little specifically in the game that is likely to be an issue. Knowledge of deck composition is somewhat beneficial, particularly when it comes to knowing when beds and other critical resources are likely to appear. It’s not a fundamental requirement for effective play.

A more substantial memory issue comes with the exploration book – players that remember what the results are of particular passages are going to be at an advantage with regards to others when it comes to picking the optimal path through the game. In something like Tales of the Arabian Nights, there are so many different story segments that this is a vanishingly small problem. In Above and Below there are only 215 different story segments and while it would be unlikely for someone to remember all of them they might very well encounter the same segments repeatedly over multiple games. Knowing the ‘correct’ path would be impactful. That said, 215 is still a large enough number to make this an issue with only occasional impact and in the end it’s almost always going to resolve down to ‘the better you roll, the better you’ll be rewarded’. Not remembering story segments is likely to be the better outcome from a game enjoyment perspective even if it may be deleterious from a scoring perspective.

We’ll recommend Above and Below for those with memory impairments, but we’d advise those with fluid intelligence impairments to look for fun elsewhere.

Physical Accessibility

There’s a fair amount of card and token management in Above and Below, but it’s mostly with a permanent impact. You don’t play a hand as such, you build up a collection of buildings, villagers and goods. Villagers are the only ones of these that require regular manipulation, although players will add goods to existing stacks as time goes by. The game does tend to sprawl considerably though, with new buildings and caverns adding to the footprint of each player. You rarely need to know much about what other people have going on in their village which means that all a player need work with is their own board and the shared offerings – but there are a good number of these. Reaching across a table to access remote parts of the game state may be required, although as is often the case this is something with which players more conveniently located can assist.

There’s also quite a lot of money manipulation since everything you buy costs money and the time of a villager, but there’s no reason this need be done using the game’s currency tokens.

Villager allocation is where most of the regular physical manipulation is done – moving villagers from the ready area to the rest/injured location. There isn’t a lot of room on the player board for this when you have more than three villagers and it’s easy to knock a villager from one to the other. You usually have few enough villagers that you’ll notice but there’s no distinction between the different areas and players will need to be vigilant.

When exploring, players usually take the villagers they’re sending on the expedition and separate them out from the others, assigning dice to them as the challenges are met. There’s not a lot of room on the cards to do this, but there’s no reason that can’t be done somewhere conveniently separate from the cave itself. All a player need to do explore a cave is roll a die (or have one rolled on their behalf) and decide the order in which dice will be rolled for their explorers. As with most of Above and Below there isn’t a lot of physical manipulation that need be done by a specific player. Reaching over so much fragile game state to aid another will need to be done with care.

Play with verbalisation is feasible, but not overly convenient. Villagers have no unique names and the specific villager you might want to send on a mission will matter. That said, they all have unique art so you can probably get away with ‘Send my brunette explorer’ or ‘Send my frog’. Buildings rarely need to be referenced except in terms of tokens that are handled in a standard way. ‘Harvest my apples’ for example, and in some cases ‘Harvest my recurring apple’ as opposed to ‘Harvest my fixed quota apples’. Those goods get assigned to cards in a systematic way. Other than this, the impact of cards is usually in terms of the incremental effect they have on a village rather than what they themselves actually are.

When it comes to reading out narrative sections, the book is much easier to work with than the one in Tales of the Arabian Nights and the passages are reasonably short so it would be feasible for one player to hold the book up for another so it could be read aloud. Some passages do lead on to others but in the event a player has physical impairments that do not permit turning the pages of a spiral book it’s possible for another player, even the one that has to choose, to turn to those passages since they are clearly indicated with large numbers. There would be no way to stop them sneaking a peek at the rewards but just don’t play with people you can’t trust.

We recommend Above and Below in this category.

Emotional Accessibility

The most frustrating thing in Above and Below is likely to be that it’s easy for your plans to fall out of sync with the opportunities presented in the game. Beds are important for reliable access to your villagers and if someone makes it a special effort to buy up those beds before you can get to them you’ll find yourself only able to deal with a subset of your population at any time.

That’s not a problem in and of itself, but the player that can hire the most villagers is going to be able to take more actions than anyone else, and those actions will also give them preferential access to shared resources. If I have five villagers and you have three, I get to do more than you do and that means more money, more adventuring, more building, and more hiring. Any player can refresh a row in the building offerings in exchange for a coin which means that nobody is necessarily forever excluded from getting buidings they need… but that’s still risk in some circumstances. Imagine you paid a coin, refreshed a row of cards to reveal four cards with beds… and you only have a single builder you can allocate to build one. Your opponent, with three builders, can buy them all and you paid for them to have the opportunity. It’s not likely that the situation will be that asymmetrical but it’s certainly possible to see key things you need snapped up by multiple other players. Every single time someone can open up a villager advantage, they become correspondingly richer and more able to take advantage of opportunities.

Other than this, there’s not a lot to worry about. Even failing a challenge in Above and Below will usually (not always) result in nothing more severe than you not getting a reward. Villagers can be injured during exploration, but only when you decide so. Nobody gets to undermine your progress in the game, they just get to open up the gap of capability between you and them.

We’ll recommend Above and Below in this category – provided everyone gets approximately equal opportunities (and that’s the usual case in my experience) it should be fine

Socioeconomic Accessibility

The manual defaults to masculinity, which is a shame. However, the art is generally very inclusive – lots of skin tones, shapes, ages, and even a fair degree of flex in gender interpretation. It’s not perfect in this respect – some skin tones are more prevelant than others – but it’s generally very good.

Above and Below has an RRP of approximately £48 and while it’s certainly not skimping on what you get in the box it’s one that comes with a (soft) expiry date. It has over two hundred story passages but it’s only a matter of time before you find those repeating, especially since some of those passages are linked to others. The game is strong enough that losing the novelty of the story telling isn’t necessarily a massive problem but you would lose the thrill of learning more about the world Below. That said, it’s not like you explore dozens of locations every game and so there will still be new things to learn for quite some time.

We’ll recommend Above and Below in this category.

Communication

The amount that communication will be an issue depends on the amount of exploration done, but there will definitely be some. The literacy level required to both read out a narrative passage and comprehend it is significant, although it will at least be done (hopefully) in an atmosphere where nobody is actively trying to make it more difficult to make out.

The game makes use of an occasionally specialist vocabulary which will make some compensations difficult. Those that are making decisions need only indicate one choice or another, but that is going to depend on the extent to which the scenario itself can be understood. That said, an ‘okay’ result is going to be available regardless of which choice is made in most circumstances. Language, articulation and hearing problems though are still going to have a significant impact on play.

We don’t recommend Above and Below in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

Where a cognitive impairment intersects with an emotional impairment there’s likely to be a considerable degree of accumulating frustration. Our recommendation in the emotional accessibility section is based on an assumption that everyone will have approximately equal access to opportunities, and that’s true if a level playing field can be assumed on a cognitive level. If one player has an ability to out-strategise another outside the normal margin of error seen in day to day life they’ll likely find their success starts to snowball. It’s not necessarily the case that everyone gets to have the same amount of fun when playing Above and Below, and sometimes that’s because another player has prevented them from getting the villagers needed to really keep up with the pace of play.

Visual impairment intersecting with a physical impairment is going to make close inspection more difficult, both in terms of gross and fine movement. For example, checking things on a player board can easily upset other things such as villager location and stacks of goods – that’s likely to be a fine-grained movement issue. Since the game sprawls considerably and there are multiple rows of things to consider, leaning over the table is probably going to be necessary to get a full appreciation of what’s available. Verbalisation and querying of the table will be possible in these circumstances, but it’s going to have an impact on game flow and occasionally gameplay intention.

Above and Below lasts about 30 minutes per player, and at large player counts it can drag on. The interleaving turns means that downtime is minimised but the differing villager counts mean that one player can easily dominate proceedings if they have a larger number than anyone else. If that’s also a player with difficulties in making a decision it can become unbearable. In larger player counts, it’s definitely a game that may last too long for it to be a comfortable choice come game night.

Conclusion

This was a considerably meatier teardown than I expected when I sat down to write it. There’s a lot going on in Above and Below, and the teardown reflects that.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | A |

| Visual Accessibility | D |

| Fluid Intelligence | D |

| Memory | B |

| Physical Accessibility | B |

| Emotional Accessibility | B |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | B |

| Communication | D |

And yes, it turns out that Above and Below definitely lives up to its name when it comes to its grades. Some things are handled exceptionally well. Other things are considerably more problematic than average.

We liked Above and Beyond to the tune of three and a half stars, and I can see potential in there that might well have pushed it even higher had a few things been more substantial than they were. Still, the only comparable game we’ve really looked at in terms of this style of storytelling game is Tales of the Arabian Nights and yeah – Above and Below is a masterpiece of accessible design in comparison. If you were looking for a game that feels completely coherent in every aspect, I might not be able to enthusiastically recommend this to you. If you were looking for a storytelling game with a good game attached then maybe you might consider whether this teardown suggests Above and Below might be worth your time.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.