| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Discworld: Ankh-Morpork (2011) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [2.21] |

| BGG Rank | 587 [7.25] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Martin Wallace |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

The Meeple Like Us project is aimed at mapping out the accessibility of a substantial portion of the BGG Top 500. One of the aims in this is to simply explore an interesting problem domain for user interaction – to nail down some stats and insights of a tractable sample of a much larger set of possibilities. That’s largely for my benefit – both personal and career. The other aim is to provide actionable advice for people looking for games that might be suitable for player groups that have complex interaction needs. That’s for the benefit I hope the site has for other people. For most games, both of these aims are addressed at the same time – we look at a game and since people can get it they know about its accessibility. For some rare games though, only half of these aims are met by a review and a teardown and in those circumstances I tend to prioritise other games . Were Discworld: Ankh Morpork any other game it probably wouldn’t get covered on the blog. It’s out of print and will almost certainly never re-enter print – especially since it’s getting rethemed as another game. If you want Discworld: Ankh Morpork you’d better psyche yourself up to pay money money money on the secondary market.

So, either you already have the game and know for yourself if it’s playable… or you don’t know if it’s playable and will likely never be in a position to buy it. Sorry.

So let me just say in advance, ‘I know this isn’t a useful review’. It’s almost unforgivable self-indulgent for me to talk about it all, but… I have a Relationship with Discworld and outside of patron newsletters I rarely get a chance to talk about it. I debated long and hard with myself as to whether I should devote the time needed for this review. I decided in the end the answer was ‘no’. But then I went ahead and did it anyway. Forgive me. Sometimes things just need to be given a chance to make their way out of your system before they curdle into something unpleasant.

Real talk now. I would have had a much worse life if I didn’t encounter the Discworld novels early on in my tweens. I can trace a direct line from the first novel in the series that I read directly to my current career. That book was Mort, if you’re wondering. Love of the Discworld novels led me to the Discworld MUD, which led me to volunteering as a coder, domain leader and an eventual administrator of the game. That experience in software development – a learning environment more effective than any you can imagine – taught me everything I ever really needed to know about development. Certainly more than I learned in my whole Software Engineering undergraduate degree.

Discworld MUD was where I learned a lot about game design, project management, and even teaching. The first teaching job I ever undertook was on Discworld MUD. I even led the Learning domain there for a while. I wrote textbooks on the development environment. That experience with coding for a live project was a major part of my pitch for my first academic job as a university teaching assistant. And it was in that first job that I met Mrs Meeple, we fell in love, and we’ve been together now for approximately eleven hundred years.

I’m a man ill-suited for any career other than academia. I’m not lying when I say the Discworld series from Terry Pratchett is the reason I’m not lying upside-down, alone and dead in a gutter, strangled somehow by my own trousers. I would never survive in a job that doesn’t come with the professional leeway of higher education. Discworld is why I have the life I have now. Who else has a book series in their life that they can credit with such a thing?

You can even directly trace the existence of this blog back to Terry Pratchett. When I left Discworld MUD I started up a MUD of my own. It’s called Epitaph and I mention it occasionally here. As part of a way to get some of my own jumbled thoughts in order when it was just me and nobody else online, I started up a blog there where I’d talk about game design and the development process I was following. That got me into the habit of posting on a regular basis, and as such it seemed like a natural segue when I started looking into board game accessibility to express my thoughts on a blog.

There you go. Terry Pratchett is to credit, or to blame, for the fact the hobby has to put up with me constantly stirring up trouble.

That’s why I need to talk about Discworld: Ankh Morpork. It makes the blog feel incomplete if I don’t. Luckily there are other things worth talking about that are a consequence of its unavailability and the framing of its setting. Other things that intensely matter in this hobby of ours.

I wasn’t into board games much at the time this was released. As such, I just didn’t think to buy it. I had the novels. All of the novels. All of the novels and a pile of the supporting books. That didn’t mean I felt the need to buy everything with a Discworld label. As such it was available for a while, appreciated or not by those that bought it, and then it slunk into unavailability. That happens a lot in board games because they’re curiously anachronistic products. We live in an age of the Internet and frictionless entertainment mediated through interweb tubes. It’s still weird to me that people are physically putting game components into boxes, packing those boxes into shipping containers, shoving the containers into ships, and then physically driving them to the back of game-shops. It seems impossibly quaint. Surely it’s should all somehow be done by block-chain now, right?

No – these things are produced in limited quantities, stored in physical places, and present logistical challenges at every link in the chain of production. As such there comes a point where you just… can’t get them any more. Sometimes just because it’s not worth the expense to reprint. Sometimes because licences expire and become increasingly difficult or costly to renew. If I want to play the original Manic Miner, I can get myself set up to do it in a few minutes even if I want it to run on a weird and obscure hardware platform. Digital games, thanks to the tireless work of emulation and preservationist communities, have a kind of immortality. Board games though are products intensely linked to time and place and if you are out of sync with either you may find yourself forever blocked out of playing.

I got my copy of Discworld: Ankh Morpork for £50, from a fellow Terry Pratchett fan I had long ago befriended on the aforementioned Discworld MUD. He sold it to me at that price because he knew I was also a fan and that I wasn’t going to turn around and try to sell it for the… £285? Really? The £285 that it currently, at the time of writing, commands on the secondary market. But what happens to other people and other games? You have to hope to luck or fate, or be willing to have a brutal walletectomy done in the name of acquiring a rare game for its emotional value. Dune is being reprinted, which is amazing, but for a long time if you were a fan of the book (which I am) you basically had to live with the knowledge that playing the game was something you’d likely never get to do. Sometimes this hobby is one characterised by wistfulness more than anything else. That the Herbert estate relented is something of a miracle.

All of this is to say that sometimes the value of a game is more than its mechanisms. Discworld: Ankh Morpork is – alright. If that were all I were looking for I’d be sorely disappointed.

It works like this – each player is dealt out a secret identity card that gives them a victory condition game state they need to bring about on the board. Perhaps you need to control a certain number of territories, or win when a certain amount of trouble is in play across the various districts of the city.

Each player has a handful of cards adorned with Discworld references, and these cards permit actions to be taken on the board or beyond. Maybe they let you take money, or place a ‘minion’ in an area. When the minions of two leaders occupy a territory, they create ‘trouble’ which disappears when a minion is removed. Players in control of a territory can buy a building there, and that building gives them a permanent bonus throughout play. The entire game revolves around manipulating minions and trouble to achieve the goal laid before each of the players.

And it’s perfectly fine and competent. Nanty Narking will also likely be a fine and competent game, being as how it’s a re-implementation of this system. If you have no great affection for Discworld as a literary property, you don’t need to read any farther. It’s an okay game and I suspect the same will be true of any game built on this framework.

But sometimes the relationship people form with games is more… intimate. There’s a reason why companies often look to bind their games to specific licences rather than invent a new intellectual property from scratch. They’re looking to transplant some of the affection felt by a fanbase into another context.

So let’s talk about fan service!

If you’re moving outside the initial canonical form of a piece of entertainment, you’re engaging in an act of fan service. Re-contextualization is a process of capturing that which you think is meaningful in a way that can be implemented into a different format. The movie versions of Harry Potter make some changes to the original text, but by and large they are relatively faithful interpretations handled in a respectful way. One might argue on the other hand that David Lynch’s version of Dune was… more problematic. I actually liked it a lot, but it invented wholesale much of its symbolism and mythos, and was derided by many as a borderline vandalistic piece of fan disservice. Fans are twitchy. Fans can be toxic. You need to be very careful when you’re looking to tap into this rich vein of enthusiasm. It predates you.

If you’re feeling cursory, you might go for an implementation that stresses recognition more than anything else. I liked Ready Player One. I know The Internet has decided that isn’t possible, but I did. It wasn’t the greatest book I ever read, but it was fun and a lot of that fun was made possible through the shallow fan-service of recognition. I wasn’t ever challenged in reading Ready Player One, but some of the enjoyment comes in simply recognising the references. Some of them were… not difficult. Every so often a subtler little gem was woven into the story and it’s always nice to feel like you’re actively being included with those little easter eggs. It’s not so much a novel as it is a scavenger hunt. It never did anything meaningful with those references. It just relied on the little dopamine rush that comes from people picking up on something nostalgic. It’s like how Stranger Things occasionally throws little homages to Ghostbusters or Pretty in Pink or the Breakfast Club. It’s not clever. It’s not challenging. It’s just… comforting.

Discworld: Ankh Morpork absolutely does this and it’s a large part of why I find it so endearing.

But there’s a real danger here, because the fans of a property are also likely to be the most discerning critics of the misuse of these references. Every time we have played Discworld: Ankh Morpork I have made a catty remark about the economy of the game. It costs $6 to buy a property in the Shades, and it makes sense that should be one of the cheapest properties given the books. However, a watch officer in Discworld earns a dollar a day. A room to rent in a clean part of the city, meals included, may be about $2 a week. So, a watch officer can buy a building outright after a week on the job or they could rent for a month at 33% more. IT MAKES NO SENSE. Boy I hope someone got fired for that blunder.

Fans are often nit-pickers and want to see their beloved franchise treated with authenticity. Mistakes by themselves may not be an actual error but enough of them add up to something worse… disrespect. It’s a double-edged sword to adapt and one must be careful they don’t cut themselves in the attempt.

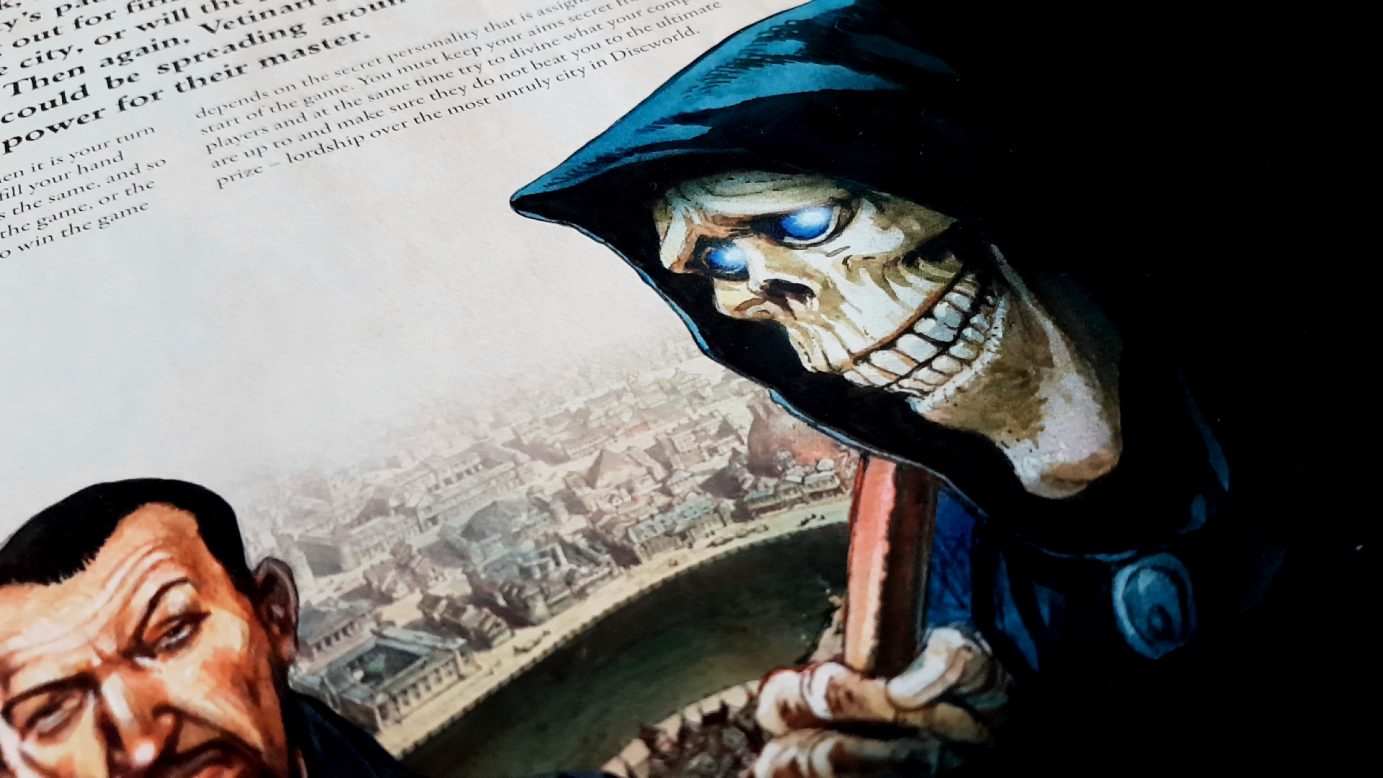

But the good news here is that Discworld: Ankh Morpork leaves you looking for things about which to nitpick because its fan service is very good. The leaders have thematic win conditions, and each of the cards you employ in the game have equally thematic effects in play. Death kills off a couple of minions when he’s employed. Reacher Gilt lets you steal a building away from someone provided it’s in an area currently experiencing trouble. Wilikins the Valet lets you place a minion anywhere you already have a building. Deep dwarfs bubble up from the undercity and can be placed anywhere. Unfortunately, they’re spelled as ‘Dark Dwarves’ when they should be ‘Dark Dwarfs’ and IT MAKES NO SENSE. Boy I hope someone – a different someone – got fired for that blunder.

But its these cards where you find the real fun in Discworld: Ankh Morpork. There aren’t an overwhelming number of mechanical possibilities but they’re all evocative. When you bring the Archchancellor of Unseen University in to accomplish a goal, he’ll end up doing something inadvisably magical which will result in a draw from the deck of random effects. Wizards in Discworld are notoriously trigger-happy and bumbling and employing one in service of a goal should backfire. That’s almost a canonical law of Discworld narrative.

The board, as a result of these events, will eventually fill up with demons and trolls and all the chaotic, good-natured anarchy of the Discworld books. Win conditions that seemed so straight-forward become wild and unwieldy because of the often competing incentives of the players. You sow trouble that others mop up because they’re aiming for something different for the city. Given the factional influences at the core of the Ankh-Morpork civic society, it comes across as a very knowing wink at the setting even if it’s not entirely successful as a gameplay device.

But…

Moving beyond the simple fan service of reverential referencing there’s something far more important that a game has to capture in order to be worthy of the highest echelons of affection in a fandom. It has to be emblematic of the spirit of a piece of work. If it manages that, it can be as experimental with the ingredients as it likes. One of the reasons why the BBC’s remake of Sherlock was effective, at least in its first few seasons, was that it captures the essence of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. I love and loved the Holmes novels and short stories. As experimental as the BBC television series was, I felt that Cedrington Bumblecatch was borderline perfect casting and Martin Freeman was an exceptionally effective Watson updated for modern sensibilities. It felt authentic even as it diverged dramatically from the source material. Often though with an adaptation you’re left thinking ‘Why even bother if you’re just going to change everything that matters?’. The answer to that inevitably is, ‘Because they’re trying to con me, a True Fan’.

The less malevolent version of that is ‘Why set yourself this challenge if you’re not going to capture anything that matters?’

Discworld: Ankh Morpork does tremendously well with recognition and even application of recognition to a meaningful game context. The cards you play make absolute sense with regards to their references. Where it does less well is in capturing what matters about Discworld. It never evokes any of the great central themes of the books. For one thing, it utterly fails to be satirical and that’s surely the first and easiest thing you’d want to implement in a Discworld game. There’s so much in this remarkable series of novels that would be fodder for amazing game mechanisms that actually said something. The themes in Discworld touch on the notion and meaning of what it is to be a person (Feet of Clay), on the structural and staid presumptuousness of organised religion (Small Gods), on belief and meaning in an unfeeling universe (Hogfather), on the rights and responsibilities of identity in an intransigent cultural context (Monstrous Regiment), and on the power of stories to shape societies (Witches Abroad). You can’t pick up a Discworld book without finding a powerful philosophical message woven through the story. So why is there no evidence of any of that here? Perhaps that’s too much of an ask for in a board game. It wasn’t me though that set the game on the back of Great A’Tuin. Those that made the decision to do so clearly thought themselves up to the task. Discworld is about ideas. It’s not about the people, or the events. Whenever Pratchett was asked about books in progress, he’d almost always discuss them in terms of the message they were intended to communicate.

More than anything else though, Discworld is a series that is chracterised by an overwhelming sense of benevolent humanity. Pratchett’s writing is full of mercy – Ankh-Morpork is often a terrifying city but kept from being oppressive by the cheerful forgiveness in every part of the series. Bad people do bad things and are punished for it but there’s never any gloating or sanctimony in the Discworld books. And yet, the game is notable for just how mean it is. The Discworld series is so genuinely positive that Death is one of the most likeable characters in the whole series of books. The take-that elements of the game certainly reflect a certain view of the politics of the city but they don’t have the same sense of meaningful and targeted malevolence that you’d find it Pratchett’s writing. The bad people in the work of Pratchett are more nuanced than that. Much of it feels just like ‘I can do a bad thing so I’ll do a bad thing’ and none of the villainy in Pratchett is ever that unsophisticated. It’s a minor thing, but one that underlines my main point – that for a game to be a truly effective implementation of a theme it has to understand the heart of the work.

In the end then, Discworld: Ankh Morpork succeeds very well in being a game about Discworld but fails dramatically in the quest to be a Discworld game. It’s a great exemplar of how to treat a franchise respectfully while managing to ignore everything that makes it meaningful.

This is a game that’s never going to leave my shelves. It captures the shallow elements of Discworld well enough that it’s still worth keeping. It’s a cautionary tale of game design though. If you’re going to hitch your wagon to something that’s important to people, you may find its greatest fans are the ones least willing to engage with you on your own terms.

Go out and read the Discworld books. And when you’ve done that, come talk to me. I’m as happy to talk about Terry Pratchett as I am to talk about board games and accessibility. Skip the first three novel if you’re coming to the franchise for the first time though. Give Mort a chance because if you’re anything like me you’ll find that’s the point at which your life becomes measurably, materially better.

Thank you Terry Pratchett. I owe you my life.