| Game Details | |

|---|---|

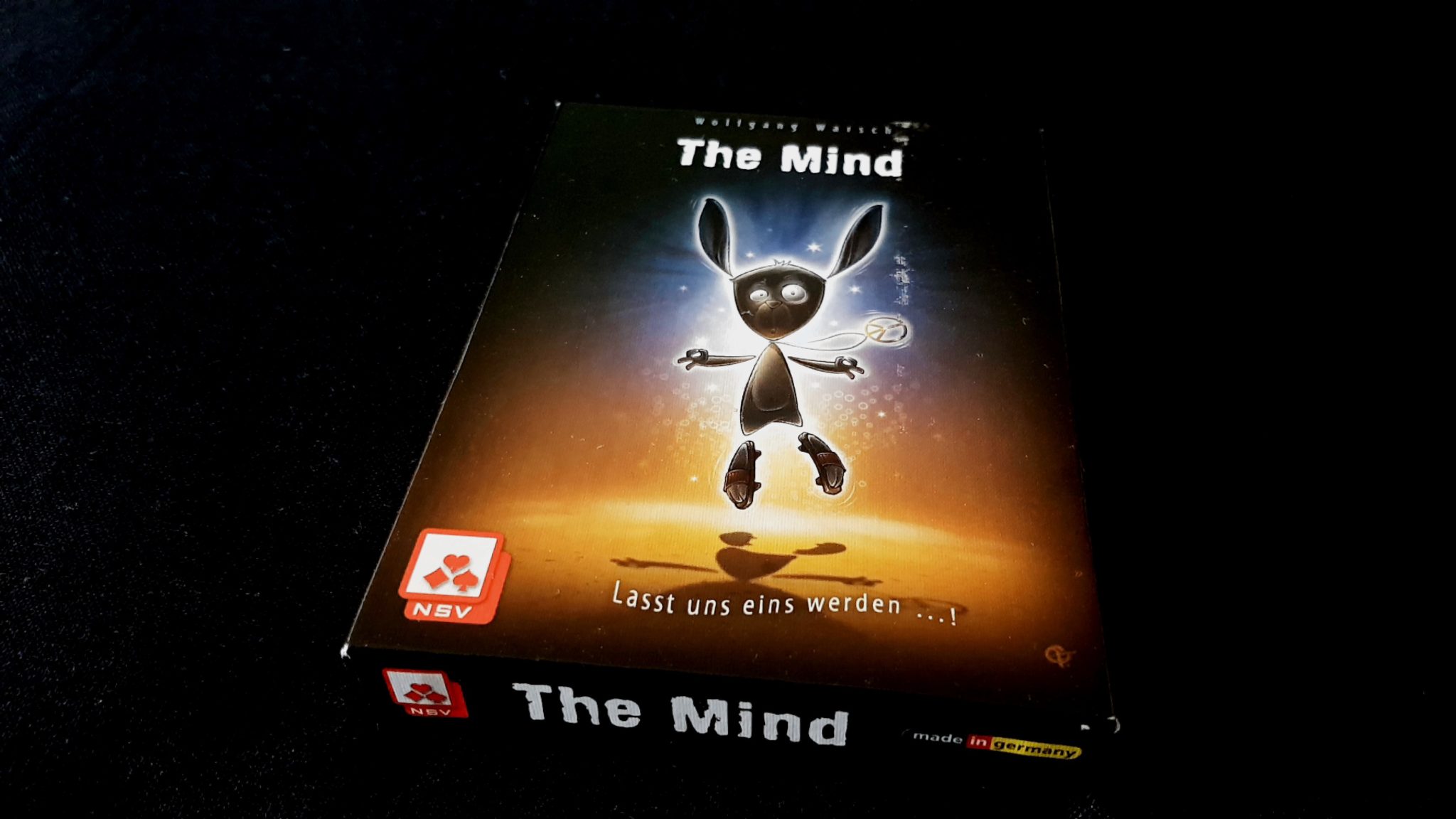

| Name | The Mind (2018) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Light [1.07] |

| BGG Rank | 950 [6.76] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 2-4 (2-4+) |

| Designer(s) | Wolfgang Warsch |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Hello, and welcome to the Meeple Like Us Curmudgeon Hour where we take a contrarian view on all the things that everyone else loves! Today we’ll be talking about The Mind. It’s a game – of sorts – that has generated the kind of enthusiastic online appreciation that I’d normally associate with a certain litigious and tech savvy pseudo-religion. People have been talking about The Mind in such reverential and devotional tones that it’s actually more than a little bit creepy. It feels a bit like watching the birth of a weird new-age movement.

‘This’, they say, ‘Is the first of a new kind of game’.

‘This’, they say, ‘Is transcendent and magical. This is the dawn of something transformative’.

‘This’, they say, ‘is more than a mere game. This is an experience that will take you a lifetime to appreciate’

‘This’, they say, ‘Will drive the Thetans from your body and grant you life-everlasting in the service of our luminous God-King’

I’m glad you got here when you did. This review was maybe a week away from becoming a seminar on deprogramming. Every time someone talks to me about the mystic experiences to be found within The Mind I look at the back of their head for tell-tale signs of a brain-controlling alien brain parasite. I look to see the antenna that picks up signals from the Cult Headquarters. I’ve felt my scalp and I didn’t find an antenna anywhere – perhaps that’s why my reception is considerably less enthusiastic.

So yeah, you probably guessed that I didn’t like The Mind much. Given our views on Hanabi and Magic Maze you probably could have guessed that before you even opened up this page. Historically we haven’t been fans of games that replace sociability with silence and that’s really where our core objection lies. We’ll see that as the review continues but I’m prepared to admit that’s not the whole story. I’m being flippant above – I do understand why people have flipped out over this odd little game.

Before we get to that let’s outline how it works.

The Mind is a collaborative game played as a team. Each player in The Mind gets a handful of cards equal to the current level of the game. First level, you all get one card. Fifth level you all have five, and so on. Each card has a number from one to one hundred. Players are attempting to communally play out their cards in such a way as to ensure they are laid down in ascending order. If they don’t manage this, the team loses a life. If they do, they progress to the next level. There’s some weirdly anti-thematic business with shuriken too but that couldn’t matter less because the game in The Mind is mostly irrelevant. Really the core activity here could be anything. It could be placing the coins in your pocket in year order. It could be ranking flavours of ice-cream in your freezer from best to worst. The cards here aren’t critical game components. They’re just an excuse.

The thing is that you can’t talk in The Mind. You have a set of cards. Everyone else has a set of cards. Your job is to convey through meaningful looks and body language that it’s almost certainly someone else that has the lowest card at the table until such time as you come to believe that actually it must be you. Your entire time in The Mind is spent making non-committal eye-contact and grimacing in horrified uncertainty like something unknown but unpleasant just crawled over your lips.

Imagine how that might work…

You put your cards down firmly to indicate that nope, there’s no way you have the lowest one at the table. Someone else looks at you and shakes their head. You raise an eyebrow. You both look at the third player who is staring at the cards with the grim determination of someone that has no intention of ever being suckered into action. The fourth player tentatively reaches out their card, checking to see if anyone else is likely to interrupt. They slowly reveal it. It’s right, or it’s wrong, and then the whole thing continues all over again.

That’s it – that’s The Mind. If you’re wondering where the game is in all of this, then I can solve that for you right now – there isn’t one. You’re not missing anything. What I’ve written is pretty much all you need to know.

‘Ah’, but its devotees say, ‘This is something that must be experienced rather than explained. You can’t understand The Mind until you play The Mind’

The last time someone said something like that to me they were on my door step trying to convert me to Jesus. That’s an apt metaphor – there is a tinge of the devotional in the way people talk about this game. That’s not intended to minimize – it’s a sincere attempt to illuminate. The Mind is essentially a faith based proposition. It promises that if you open yourself up to the experience you will find yourself moved by the insubstantial and ineffable qualities that defy the rational. For a lot of people that seems to have been true – in participating they have found themselves enchanted and entertained beyond the mechanisms of the box. I’ve tried it with a lot of people though and I’m yet to find myself even passably diverted by the task.

Now, before I dig down into the why of that I want to at least say something positive here. I’m genuinely impressed by how unabashedly experimental The Mind is. I’m very pleased to see a game like this exist even if I can’t possibly recommend it to you. The Mind is essentially the tabletop equivalent of the video games sometimes derisively called ‘walking simulators’. Games like Gone Home, or Dear Esther, or the Stanley Parable. I’m absolutely fine with games like that existing – in the past I’ve tried to redefine ‘walking simulators’ as ‘empathic puzzlers’ because what appeals most to me is that they change the whole expectation of interaction. They become riddles of emotional understanding rather than of logical deduction. They eschew formal systems and mechanisms in favour of a more resonant and spiritual relationship between player and game. It becomes about acceptance of the echoes of its characters, the immersion of its spatiality, and the vibrations of its atmosphere. These games are about being, not just about doing. They externalise the meaning so that it exists in the player rather than in the game. At the end you haven’t accomplished anything other than expanding your understanding of an often complex social and philosophical scenario. The puzzles in these games aren’t to be beaten – they’re to be understood.

That’s The Mind – it’s basically an excuse for you to stare at the people around you in increasingly tense and comic ways. Absolutely none of the game is in the cards you get. It’s all in the elasticity of the social context that emerges around the table. It’s all to be found in an uncertainty and unwillingness to commit. That’s a natural consequence that comes with people trying to do something precise under precisely unknowable circumstances. All your decisions exist on a probability curve. If you have the one, there’s no uncertainty. If you have the one-hundred, there’s no uncertainty. The closer you are to the last card that was played, the less uncertainty there is. The frisson of excitement that you get here comes when everyone has approximately equal uncertainty and no way of reducing it other than committing to action that might be misguided. Every gesture in The Mind is an attempt to get someone else to do the brave thing and lay a card down. However in all those winces and grimaces you can get a feel for what uncertainty means, and there are times when that uncertainty can coalesce into an almost certain and spooky knowledge of where everyone is with the cards they have. This is a game where you’re all collaboratively building a vocabulary around hesitation.

At its worst, The Mind is a game of playing percentages. At its best, The Mind is a game of an emerging consensus of synchronicity. It’s a growing shared understanding of what reluctance to play means and how that translates into concrete actions It’s not a game of counting or secret signals even if that’s almost certainly going to happen in a lot of cases. At its best it’s about silently and collaboratively finding a rhythm that can lead to outcomes that look borderline mystical. I play my sixteen. You play your twenty. Pauline plays her twenty-six. I play my twenty-seven. Everyone has a sharp intake of breath and the near miss causes a moment’s subconscious re-evaluation. Every game of The Mind begins with a piece of pantomime – you all put your hands in the centre to find your balance and then you begin to play. It has all the trappings of ritual and in that context it’s not surprising that people have found it to be such a magical experience.

But again – that’s nothing to do with The Mind. There are any number of theatre improv or classroom exercises that accomplish the same thing and don’t charge you for the privilege. A game of The Mind watched from the outside doesn’t so much feel like watching a séance as it does a scene from Whose Line Is It Anyway. Still, I can see why at its best the Mind would move people to become advocates for its cause. You truly can only appreciate something like this through participation.

The problem is that I think many people will see The Mind in more nakedly mechanistic ways, and that reveals the intense problem at the core of the game. If you’re not willing to be swept away in the semi-mystical trappings of telepathy you’ll be a lot more critical about what you end up doing.

I loathe the term with a passion, but we’ve spoken about analysis paralysis a number of times on this blog. It’s when you are left in a state of indecision because all of your options are valued approximately evenly. You have to commit, but don’t have a clear understanding as to which action you should. Logically if all options are equal you should just pick one and have done with it but that’s not how people approach games. Games permit an illusion of control that is hard to abdicate to the unthinking vagaries of probability. Analysis Paralysis (or AP) isn’t really the problem though – the problem is that it creates circumstances for downtime for other people. Downtime is the period of the game where you’re not actually involved – just time you’re waiting for something to happen to influence the game state. Downtime isn’t the same thing as not being the active player – the best games let you meaningfully plan out your future actions when it’s not your turn. Downtime is the span of time between the moments when you get to have fun. It’s the most boring part of any game. The problem here is that The Mind is an attempt to turn downtime into a game mechanic.

As I said above, that’s bravely experimental – it’s something I have never seen any game attempt before. Sometimes though the reason why you’re striking out into unexplored territory is because there’s nothing of value to be found there and everyone knows that but you.

Here’s a little thought experiment for you, drawn from my own real-life experience with the game. What happens is there is no convergence towards a shared understanding of timing? What happens if people look at the uncertainty of the decision space and simply shut down? What happens if a ten has been played, your card is a ninety, and nobody else plays a card? What if nobody plays a card for whole minutes. Worse, what happens if it is mathematically impossible that you have the lowest card and yet you can’t actually communicate that information at all? What happens if you have the ninety and someone else has the eighty-nine and neither of you will budge? Within the Mind there is no guarantee that you’ll ever get to the point where you’re all in sync. There’s no guarantee you’ll ever get past the first hurdle of learning how to convey information through indecision.

There is a point where the uncertainty curves back inwards. Where you are so far away from the number on the table that you can be reasonably sure that you’re not the person to play. That point differs from person to person, and it’s entirely possible that someone has a thirty versus the ten on the table and is still unwilling to play it. You can only coerce them with your eyes and meaningful gestures. You can’t get out a chalkboard and calculate the odds for them or say ‘Seriously, it’s you’.

Sure, you can stare at them but the problem is that you don’t know what cards they have. They don’t know what you have. You can easily get stuck in a stalemate where neither party is willing to accept responsibility for play because in the end any exhortation for someone to do so is an act of faith and trust. If that’s missing then the whole thing breaks down in irreparable ways. When someone is just as convinced as you are that they don’t have the next card then the downtime can become a rigid barrier that just gets more rigid the longer it goes on. When nobody can be coerced to play, then the whole thing shuts down until someone simply gives up. you can look at using one of the shuriken that lets everyone get rid of their lowest card but even that’s an act of consensus and it just kicks the problem down the road a little bit.

So – your exposure to the game is likely to fall into one of two possibilities. The Mind might be a fulfilling experience of coming to an unspoken agreement regarding pacing. It might be a grim, tense affair of stubborn silence and weaponised downtime. For me it has been almost exclusively the latter, and the one time it might have been otherwise got cut too short for it to be convincing. We can’t provide a review for the Mind based on how other people have found it, though. We have to give you the conclusions to which we arrived based on our own exposure.

Reviewers and critics are often terrible people to turn to for guidance, regardless of what we’d like our roles to be. For reasons I’ve discussed in the past it’s much easier to write a positive review than it is to write a negative one. However it’s also easier to write about a game that is interesting and original than it is to write about one that is mechanically solid but uninspiring. That creates a pair of intersecting biases that I think skew coverage of things like The Mind.

It’s unique and interesting and original and it’s more fun and easier to talk about how that’s great as opposed to how it’s not. More than this, when you’re taking a contrary view you run the risk of outing yourself as the simple schlub that ‘just doesn’t get it’. That’s why movie critics enthuse about films nobody wants to watch. After years of doing the job it’s hard to get excited about new versions of what you’ve already seen a dozen times before. When you’re sitting in the audience for a movie that is borderline incomprehensible it’s hard to be the person that says ‘Actually, this is bollocks’ when you know everyone else has positively melted over the rich symbolism and inspired cinematography. There is a touch of the Emperor’s New Catan in all of this.

I’m not going to say that anyone is wrong for having reviewed The Mind as positively as I’ve seen. I’m just going to say that what most gamers look for with regards to their fun is not the same as what most reviewers look to with regards to their function. Uniqueness is an affordance for reviewers – it’s like the handle on a door. I believe that the ease with which The Mind permits us to focus on its originality means that it’s easy to miss out on the other things that are more important in the greater ecosystem of gaming. We focus on that property because it’s the one that is most clearly expressed and the one that we can talk about with most enthusiasm. Sometimes a bold experiment though serves only to show that the underlying thinking is flawed, or at the very least, cannot be extrapolated to real world circumstances. That doesn’t mean the experiment was wrong – failure is a vital part of pushing the boundaries.

It would have been so much easier for us to write a review that went with the grain instead of against it. Progress though requires us to be honest about what we think works and what we think doesn’t.

Plenty of people think The Mind works. We don’t. Use that information in whatever way you feel helps guide your decisions.