| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | The Quest for El Dorado (2017) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [1.94] |

| BGG Rank | 120 [7.68] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Reiner Knizia |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

The mechanism of deck-building is undeniably effective – it’s such a clearly satisfying system that it’s hard to go too wrong with it. Imagine a poker deck-builder where with every hand you get rid of a bad card from your deck and replace it with a better card, sometimes with extra powers. I’d play that. The mechanism is so robust that it’s difficult to go wrong with it. It guarantees a certain amount of fun because it feels satisfying to level a weak deck of cards up into something extraordinary. The Quest for El Dorado is a racing game built upon a deck-builder, and it’s very enjoyable. Those of you that are familiar with the landscape of hobbyist games can probably stop reading here. Bye!

Oh, hello – you didn’t want to take advantage of the offer to duck out early? Good. That means you’re either a Meeple Like Us fan, willing to brave word counts larger than your average Buzzfeed article. Or, if you’re not… you’re probably in the intended audience for a game of this nature. Perhaps you’re one of people that read that introductory paragraph and came away with one main question – ‘What exactly is a deck builder and why is he talking like it’s something I should already know??’

You’ve come to the right place.

There’s a level of expected game literacy required by the introduction of a particular mechanism. There’s also usually a disconnect between how easy something is to understand and how difficult it is to really master. Someone can tell you how all the chess pieces move. It’s not that difficult. Moving them in the right way to accomplish useful things takes a lot more consideration. I think that’s also true of deck-builders, and few of them really go out of their way to ‘on-ramp’ new players in the conventions of strategy. Inevitably they require play with training wheels, with someone explaining not just the what but the why of play. That’s not helped by the fact a lot of effective strategy in a deck builder is counter-intuitive.

The oddly self-destructive nature of good deck building leads to some common questions.

‘Why would I want to get rid of a card I bought?’

‘Why wouldn’t I want to just buy the best card I can afford?’

‘Why wouldn’t I want to get points? That’s how you win?’

The fun of a deck-builder comes from things like enforcing precision in a deck through curation, through enabling situational synergies, and from ramping up and down at the right point. It’s all about creating the circumstances for elegance so that you gracefully slide into first place rather than lose steam and stumble before you reach the finish line. The core mechanism is simple – ‘get rid of cards, buy new cards to replace them’. You can’t expect that to be enough for people that maybe haven’t had a chance to sit down with the system and really work out its intricacies.

So, for those of you still waiting for the description of a deck builder, here’s how the Quest for El Dorado works.

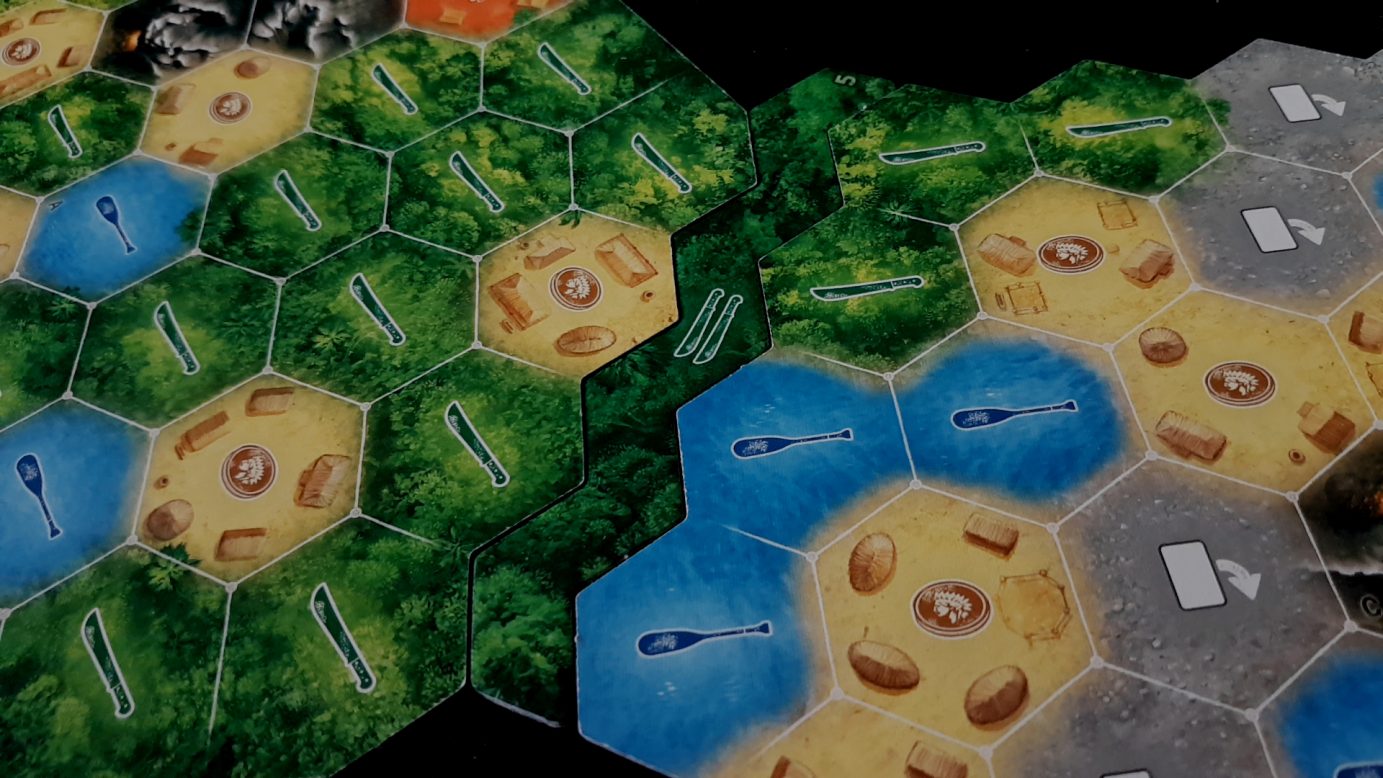

Each player starts with a deck of eight cards. They’ll draw four of these into their hand each turn, and spend those cards on one of two activities. They’ll use their allowance of movement to make progress across the board, and they’ll use the cash they deal out to buy better cards from a central marketplace. Each hex on the board requires a certain amount of a particular kind of movement, and while movement ‘rolls over’, every hex requires a single expenditure of a card to enter. You can use a card that provides two movement to move over a hex that costs one, and then another hex that costs one. You can’t use a two and a one to enter a three space – you need a card with at least three movement. Some hexes let you use any card to enter, but those ignore the face value of the cards. You discard a certain number and enter the area.

Every card you play leaves your hand and gets put into the discard pile, and that’s where every card you buy goes. You pick it up from the marketplace and then throw it directly into the nearest bin.

When you’ve run out of cards to draw into your hand, you take your discard deck and shuffle it. It then becomes your new draw deck, and the cards you have previously bought will begin to cycle into your hand. In the Quest for El Dorado you might be in South America but the only available Amazon doesn’t offer next day delivery. Nothing gets delivered by drone. You need to wait for your parcels. Everything happens on a delay and managing that is a key skill in playing a deck builder.

That may seem awkward and annoying until you realize what’s happening every reshuffle is an acceleration. With every new card you’ll find yourself getting better options. You’ll buy cards that take you farther, or that can be used in a lot of different ways. You’ll eventually get cards that increase the number of cards you can hold at once, or that let you permanently trash cards you’ve drawn. You’ll get special one-use cards that are extraordinarily powerful but gone as soon as you play them. That emaciated deck of frustrated ambitions will eventually become the stuff that dreams are made of – tight, lean and able to take you quickly where you want to go.

The aim of the game is to be the first to enter El Dorado with all its fabled riches, and as such that deck has a job to do – to get you through the mixed, twisting terrain as efficiently as possible so nobody gets to the goal before you. There are other temptations though, The board though is littered with caves, and those contain special one-use powers for which it might well be worth taking a detour. Or maybe not. You might gain a leg-up on an opponent but you might end up with something that you don’t need or want. It’s a gamble, but sometimes a worthwhile one. Many of the treasures you find will be cursory, but some are extraordinarily helpful in a pinch.

This is s a fun game – lighthearted and occasionally perversely funny. Being stranded at one side of a very small river because you don’t draw any sailors is comic. Tragic, but comic. That comedy can be elevated when you watch someone else unable to make any headway through a light forest because they stacked their deck with expensive sea captains. The nature of the modular board means that, if you set it up properly, delays at one part will be compensated by a surprising turn of speed at others. The end result is that players tend to be arriving at the conclusion at approximately the same time and that’s always good for an exciting photo finish. It’s a satisfying, good-natured game and while not something I’d be inclined to pull out for every game night I certainly wouldn’t grumble at someone wanting to give it a go.

It’s not really in the game though that Quest for El Dorado really shines.

You may or may not remember when I talked about Mint Works and basically said it was like a tutorial level of a video game where the basics of worker placement were being taught. I said that I saw a useful market for a series of games that acted as ways to safely expose people to more complicated game mechanisms. The Quest for El Dorado is a perfect example of what a good game like that might look like – fun in its own rights but most interesting for the way it builds literacy in its systems.

A game like Dominion, while undeniably laudable, is also a victim of its own abstractions. You use a merchant to access a workshop, spend that workshop and a coin to buy a market, later use that market to access a remodel which you use to buy another market, and so on. You can layer clever synergies together and build very creative decks from any Dominion set but it’s all very… academic. It’s a game you play in your head, not in your nerves. The names and associated abilities of each card don’t really make a lot of intuitive sense. They don’t lead the player to greater enlightenment. That has to happen independently of the game framing.

The Quest for El Dorado on the other hand strips out a lot of the clever complexity of deck building and focuses on the most satisfying and instantly understandable aspects:

- Draw more cards

- Draw better cards

- Get more money

- Claim cards without money

The only ‘advanced’ deckbuilder mechanism it permits is scrapping cards, and its own design illuminates why you’d want to do that. There you are, in the dark jungle leading towards El Dorado. All you’re drawing are photographers – those give you money or mobility through camps. You don’t need new cards any more and civilization was a long time ago. What you do need is convenient access to the jungle movement cards you already own. Your eyes alight on the marketplace, full of new cards that would let you trash the unwanted detritus of the past from your hand. It instantly clicks. ‘I know how all of this fits together’. You don’t need anyone to give you a lecture on deck curation. You see the need for it and learn its value viscerally. It grounds this insight in a concrete context. You have an epiphany – you discover this fundamental truth for yourself and you can feel proud for having done so.

On top of this, the Quest for El Dorado even encourages a degree of forward planning through the layout of the hexes. They become increasingly difficult to work through as you get closer to the goal, and so you also learn quickly the importance of efficiency. Because you can’t spend cards in a set to enter a hex, you soon find out that four cards with one movement isn’t a patch on one card with four movement… and for reasons more subtle than you get more cards to play with in a hand. You’re taught, by the spatiality of the board, to hack away at the weaker cards you have with a ruthless absence of sympathy. The board has numerous base camps where you can do this without having a scrapping card in your deck. The first time you enter one of those will be jarring. The next time will be cathartic.

By the end of a game of the Quest for El Dorado you’ve learned enough about a complex mechanism to play any subsequent deck-building game with confidence. It’s a remarkable trick of pedagogy – to include genuine praxis in a box of cardboard components.

It would be unfair though to cast this simply as a game for beginners, because the design here is satisfying for more experienced gamers to enjoy too. The marketplace of cards for example has an unusual design in that you can only buy cards that are in the market row. Once a space there is empty, the next person can buy from any of the stacks, including those not in the market. If they buy from a stack that isn’t currently for sale, you fill the space on the row with what’s left of that stack. If you know everyone wants to buy a captain, or a prop plane, you can slip in and make sure the only new option they get is for a journalist. Cards sell out rapidly though, so at most you can slow people down and you can never genuinely block them forever. Still, it’s a neat tool you have for shaping the way the race shakes out.

The topology of the terrain too gives opportunities for strategy. Players can’t move through mountains or through other players, which means that your presence is blocking. So you can stand at a critical entry-point to the map and hold everyone up, or force them to go a more costly route by making sure you’re constantly in front of them in the easy terrain. You can be the annoying little brother blocking the television, or a bouncer forcing people to find another way into the club. Sometimes your reticence to move can be strategy all of its own – a point that will come up again in the teardown.

I wouldn’t go so far to say that Quest for El Dorado is a great game, but rather a game that under the right circumstances can do a great thing. It can be the first, comfortable step someone takes towards understanding a sophisticated game mechanism. That will open up a whole pile of other titles as possibilities for game night. It turns out the real El Dorado you’re racing towards is the glittering golden sunlands of being able to encourage your friends towards playing some of the best games you’re likely to have on your shelves.