| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | 7 Wonders Duel (2015) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [2.23] |

| BGG Rank | 19 [8.10] |

| Player Count | 2 |

| Designer(s) | Antoine Bauza and Bruno Cathala |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Do you like the idea of Splendor’s core game design, but really wish it had a mechanic where you could metaphorically punch your opponents right in their metaphorical dumb faces? Man, do I have a game for you!

Are we going to do that thing where we say ‘ten paces’ and then one of us turns after four?

I’ve never played the original 7 Wonders, so I am spectacularly ill-equipped to answer the obvious question of ‘Which game is better?’. Seriously, you’d be better asking a monkey because while it wouldn’t give you a better answer it might do something hilarious to make up for it. Actually, that’s a general piece of advice I’d give anyone – don’t ask me, find a monkey.

The Splendor comparison isn’t a random digression here – the heart of 7 Wonders Duel is an engine builder that works in a very similar way to that top rate title. You collect cards to build up the infrastructure that allows you to collect better cards. Bolted on to this is a very nice system of exploring a possibility space of card availability. This is attached to an abstracted war for domination. That in turn is coupled to the development of the philosophical and scientific principles that will allow you to claim, at the very least, the moral high-ground of intellectual accomplishment. And, as it is explicitly a two player game, it works great for couples provided you don’t really like each other – like the pointy end of a dagger, this game can draw blood.

You are losing a wonder race

Players are competing for victory over the course of three ages, and along the way they’re going to be trying to construct the four wonders they picked up in the early stage draft. Only 7 of these can be constructed during the game, and they confer considerable advantage for the player that brings them into play. Some let you take an extra turn (like the Sphinx). Some let you destroy the cards your opponent has painstakingly collected and lovingly placed (like the Circus Maximus). Others just give you a hefty victory point boost, such as the Pyramids. All of them are expensive to build, all of them can change the flow of victory.

I’ll make a path to the rainbow’s end

Players select their wonders, and then the battleground of the game is set. Five ‘progress’ tokens are put into play, selected randomly from a pool of nine. A war token is placed in the centre of the scoring track. As military buildings are constructed, it’ll move forwards and backwards like the crying child in the centre of a brutal and blood-soaked tug-of-war.

I’ll never live to match the beauty again

When this token gets deep into one player’s territory, that player will lose money as a punishment for their lax adherence to the principles of proportionate defense. If it gets too deep, you lose the game instantly. You’re conquered by the invading armies of your opponent. So you better keep an eye on your military and make sure you don’t fall too far behind in the arms race. You’ll be fencing with your opponent in this way throughout the game. If you let the momentum of play get away from you you might find yourself watching your defeat with all the futile resignation of the French observing the Nazis march through the Arc de Triomphe.

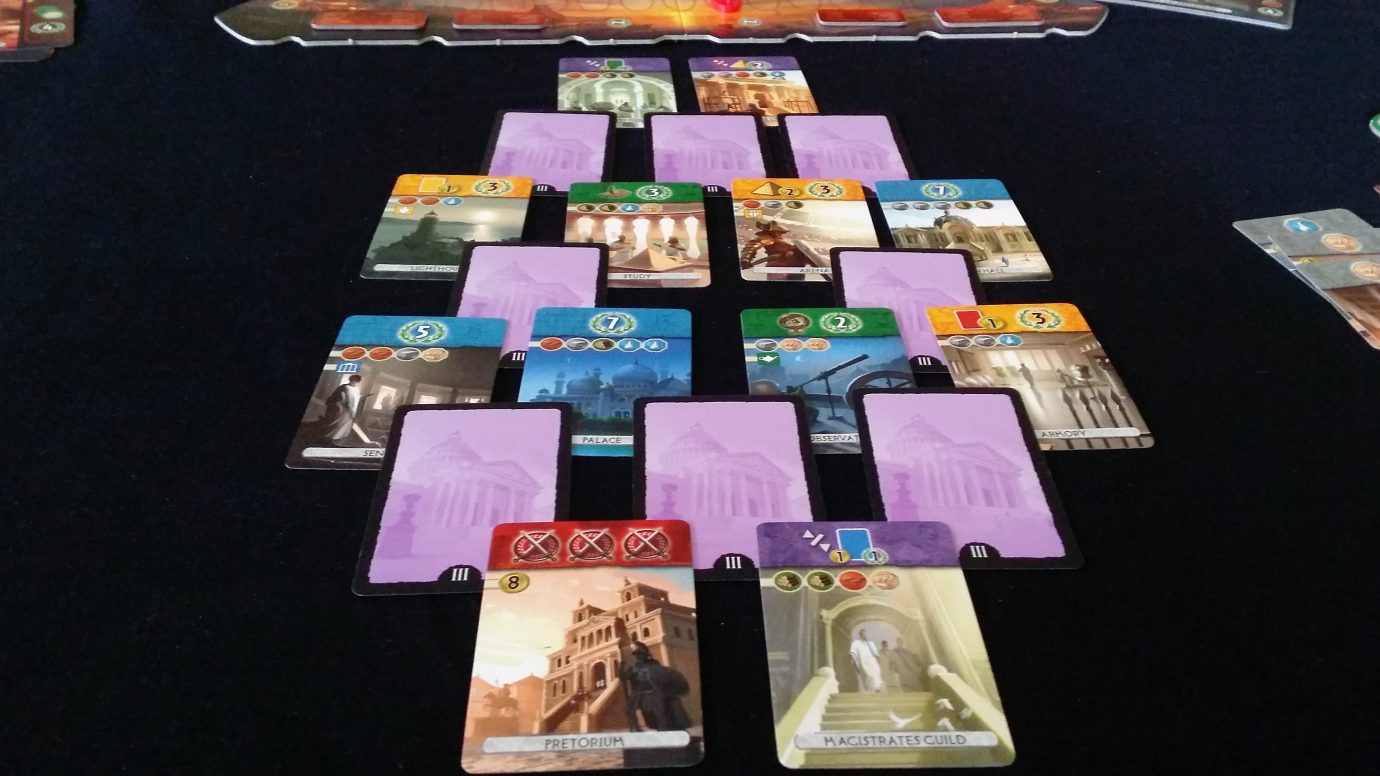

For the rest of the game, you’ll be working your way through one of three trees of cards, the disposition of which is decided by a random shuffle and a pyramid based distribution which reveals some advancements while obscuring others:

I’ve built a pyramid of my own here.

This is the structure for Age I. We begin at the bottom, collecting the cards we can afford. As we remove the cards pinning down those above, we flip them over to reveal what may be found underneath. When we deal out this pyramid, we remove three cards from the deck and discard them entirely from play. We won’t be seeing them at all during this game. We may have a fair idea of what’s on the obverse of the face down cards then, but we can never know for sure. That’s the heart of the puzzle that 7 Wonders: Duel puts in front of us, and it’s easily its best feature.

Seize the means of production, citizens!

Each of the cards is going to give us something for building it. That delicious treasure is indicated along the top. The logging camp will give us wood we can use for building other structures. It’ll cost us one of the seven coins we get at the beginning of the game to claim it, but we’ll reap the benefit for the rest of the session. The quarry gives us a stone resource, and it’s free. Free, I tell you. The lumber yard also produces wood, and it is also free. We take it in turns to pick the cards we can afford, and add them to the city we’re constructing in front of us. Our first priority is to procure a supply of resources, because as the ages go on we’ll find it harder and harder to acquire the means of producing raw goods.

The fact that we take cards in turn makes every choice important. The simple fact is that we want everything that’s there. It’s all great. There isn’t a dud in the deck – every single thing in that layout is worth salivating over. When we take a card, we know our opponent is going to deprive us of another that we want with exactly the same intensity as our first. Look at the riches on offer for the first turn – a quarry and a lumber yard are both excellent to have, but we can only pick one because our opponent… Yes, they’re going to take the other one we wanted, because they are total bastards. We’re left then with paying a gold piece to get the logging camp if we want wood. And we do, because resources are how we build the increasingly excellent structures that become available as we progress through the ages. Not only that, the cost of procuring goods we don’t have is directly dependent on the number of goods produced by our opponent. Oh god.

Oh god, what should I do, OH GOD?

But do we want this? I mean, it looks like we do but this is a game not just of building an engine but of controlling the gradient of revelation. If we take that logging camp, we’re going to reveal the two face-down cards it’s currently pinning. What if those cards are even more excellent than the one we take? If that happens, all we end up doing is giving our opponent the first bite of an increasingly succulent buffet. Oh god, what to do?

Cards in 7 Wonders: Duel also have other features we need to bear in mind. Some cards represent places of knowledge and learning – those are marked with a green border, and come with a symbol of scientific accomplishment. If we can get six different scientific symbols in our hand, we win – we’re the smartest, and presumably we leverage our smarts into the nuclear annihilation of our dumbshoes foes.

I don’t have time for your book learnin’

More than that, if we can get two matching symbols we get to claim a progress token of our choice, and those are like civilization power-ups. They add new and potentially overwhelmingly powerful bonuses to our budding empire. They might strengthen the power of our military buildings, give us free money, reduce the resource cost of construction, and more. We want those, and we want to keep them out of the hands of our opponents. Those two things will often require contradictory strategies.

Or perhaps we want to control the mercantile opportunities of our competing nations. For that, we’ll want to grab the yellow cards.

It’s all so enticing!

If we don’t have the resources we need to claim a card, we can buy them in – but it’ll cost ya. Resources cost two gold, plus an additional gold for each unit of the resource your opponent produces. If you have no clay, and they’re producing four clay, it’ll cost you six gold for each clay resource you buy in! Ouch. However, if you bought the clay reserve you can purchase clay for a flat cost of one gold per unit. Why even bother producing it if you can buy it at those low, low prices?

Or maybe you want to rattle your sabre a bit. The stable would be excellent in that capacity. You need to be producing a wood resource to build it (or be prepared to shell out the cash), but it’ll give you a shield token and that’ll allow you to march the war token one space towards your opponent’s capital. It’ll also be useful later on – that white horseshoe will fulfill the building requirement of a later card.

So, what’s the best card to buy? That’s going to depend on a number of things. You’ll need to keep an eye on the resource requirements of your wonders, so you’ll probably want to collect cards that play to those strengths. But you’ll also need to keep an eye on the war token, so you’ll probably want to collect cards that ensure you have a viable military. But you’ll also need to keep an eye on scientific progress. So you’ll probably want to collect those cards too. And you’ll also need to keep an eye on each of those elements for your opponent, and make sure that the cards you pick minimise potential opportunities for the enemy. Every selection that would reveal a face-down card is an exercise in tentative risk management. You won’t be able to pick any of the ones you reveal, so you just have to hope you didn’t hand your opponent a stick with which to beat you. When you are on the verge of being invaded, knowing there is probably a military card face down in the tableau somewhere, you approach the act of revelation with the same delicate care as a bomb disposal expert approaching a ticking package.

Phew, it didn’t explode

Over time, you collect cards together to form the bones of your empire. You spar with your opponent over the military cards, and you compete to be the first to make scientific progress. For all the simplicity of the mechanic, it does a very effective job of creating the impression you’re building something grand and continent spanning. Each card represents an opportunity to either double-down on the strengths of your civilization, or compensate for its weaknesses. Your society develops a personality, with its own complex neuroses and insecurities.

Games can feel very different depending on how the revelation of cards treats you. In one game, I found myself bereft of wood (that’s what she sa… oh god, I am so sorry) – Mrs Meeple had tied up not only the production, but also the access to cheap trading routes. I found myself unable to take advantage of the opportunities the age was presenting me because I didn’t have the money to compensate for a weak engine of production. That in turn needed me to adopt a more ruthless approach to the cards. I needed to get rid of those cards likely to add fuel to an increasingly tense situation. I had to approach the tableau like it was a forest in need of a controlled burn.

You don’t have to buy cards, you see – you can also burn them to the ground in exchange for money. You get two gold for each destroyed card, plus an extra gold for each yellow commerce building you have. You can use this income to compensate for otherwise untenable situations, or tactically remove cards that are especially good for your opponent but otherwise unaffordable.

Selection is getting a little sparse

As the first age gets to its termination, the opportunities start to contract. You begin with lots of choices, but they rapidly disappear as they funnel towards the end. Early turns don’t necessarily lead to players competing especially bitterly because there’s an embarrassment of riches. Later on though, play has to become more tactical, and it has to be undertaken with a consideration as to the coming age…

This is the dawning of the age of Aquarius

7 Wonders: Duel is played over three ages, each making use of a different deck. In the second age, we encounter more powerful buildings with richer rewards but with correspondingly greater cost. We also encounter a different layout which changes the flavour of advancement – we begin with fewer opportunities but open up a numerically greater number of choices every turn. The very first card you pick in the second age is going to open up a hidden opportunity, so you’d better hope it’s not going to be a game-changer.

These look tasty

In the second age, we also encounter the concept of linking. Look at the library here – it costs a stone, a wood, and a beaker. That is unless you have a card which has the white book symbol on it. If you do, you can just pick up that card for nothing, which is so spectacularly satisfying it’s a reasonable proxy for sexual intercourse.

This library does DVDs too.

And look! Player two has that exact icon in their city. And if they can get that card, they’ll have two quills and that will give them one of the powerful progress tokens that are in play for this game. Player one best not let that happen, even if they have to burn an opportunity of their own to prevent it!

Is it too late to talk appeasement?

But on the other hand…

As this particular second age comes to an end, conflict is going to increase. There are three seriously unpleasant military cards at the end of this age. Six shields aren’t enough to march from the centre into a player’s capital, but it will take you distressingly close. So you probably want to make sure your own military is in a good enough state to prevent that happening should the momentum of play go against you. And if in the process you set yourself to trigger an assault they just can’t halt? Well, wouldn’t that be just peachy?

So what do you do? What’s the best route for your fledgling empire? I honestly have no idea!

It gives you a certain sympathy for real world leaders, juggling limited resources to meet a number of equally important goals in the face of a hostile media and a whiny, self-indulgent population of malcontented… sorry, I think I distracted myself there.

Really, what you need more than anything else is an asymmetrical advantage. One that you know could decisively alter the balance of power in your favour. If only you had something wondrous you could do to claim the initiative…

OH YES!

The third thing you can do with a card is convert it into a wonder. As long as you can meet the building requirements, you take the card you picked up (for free), slip it under your wonder, and then boom – that’s yours now. The right wonder can dramatically change the course of the game. The wrong one? Well, the only thing you’ll wonder is ‘why did I do that?’’

This will make a lovely tourist destination in several thousand years

Only seven wonders can be constructed over the course of the game, so in the best case scenario someone isn’t getting to build one of theirs. You’d best get a move on if you want to get the maximum advantage out of your mighty erections. Some of the wonders have timing implications too – some wonders you’ll want right away, others you’ll want to keep in reserve to the end. Others you’ll want to hold back until exactly the right time, even if that time may never come. Some wonders synergise very well with certain cards, other synergise excellently with the opportunities of the age structure. Several wonders, for example, permit you to take an immediate second turn which might very well permit a combo of cards that can absolutely wreck an opponent. It’s possible, if you know what you’re doing and build your empire for it, to build a wonder, take another turn, use that to build another wonder, and then force your opponent to discard a production card at the same time you take a step towards their capital. It’s unlikely that will win you the game, but it’ll certainly undermine whatever strategy they had in mind. The right wonder combination is like throwing a Molotov into your opponent’s headquarters – they’ll suddenly need to invest all their attention in fire-fighting.

As the age progresses, you’ll be able to draw considerable satisfaction from the infrastructure you’ve built in place. It’ll have production, military potential, scientific accomplishment and even some recreational buildings that contribute nothing but victory points. It’ll be yours – something you built with your own two hands. Admittedly, only from cards, but every global power has to begin somewhere. Why not at your kitchen table?

I call this city – Meepopolis

And then almost as quickly as it began, we finish the second age and move inexorably into the third and final age of advancement:

The final age of humanity!

The structure of the third age is one of choke-points – not enough to seriously influence the nature of play, but a bifurcation of opportunity that is going to texture the risk and reward of revelation. It spices things up a bit, but not so much that it substantively alters the flavour of the meal. In the third age, we also encounter a few ‘guild’ cards – their only job is to change the victory point calculations at the end a little. That can be enough to eke out a victory in a close game, but as usual they’ll come at the cost of something else you really wanted. Like for example, an especially effective aggressive intrusion into your opponent’s territory. The further you are all up in their bid’ness, the more victory points you’ll gain at the end. Which card is better? Oh god, who knows? It’s all so stressful.

At the end of the third age, all the victory points are totted up, and victory is claimed. That is, assuming the game didn’t end in the lamentation of the dead as a result of an invasion. And also assuming that it didn’t end in the ignoble humiliation of scientific irrelevance. When you play the game of Duel, you win or you die. Or I guess you just lose. It’s really not quite as cutthroat as all that. The end scoring is a little fiddly, and you are entirely justified in a moment of dull horror as you open the box and see that it comes with that dreaded implement of ‘pain in the cornhole endgame scoring’, a pad for the arithmetic:

I would have rather seen a massive spider, if I’m honest.

I love 7 Wonders: Duel. It’s more complicated than Splendor, and with a steeper learning curve, but it scratches exactly the same itch and does so, for me, more deeply and effectively. It’s not something I’d break out to introduce people to table top gaming, but it’s definitely the kind of thing I’d reserve as a special treat if they’d taken to the experience with the appropriate enthusiasm. Splendor is an easily appreciated house wine that everyone can enjoy. 7 Wonders: Duel is a slightly more rarefied vintage that needs a degree of deeper familiarity to fully appreciate. It doesn’t obsolete Splendor by any stretch of the imagination, but I do think that the two of them are shouldering each other aggressively out of the way in a bid to attract the love and affection of the same group of people.

It’s a visually stunning game too – the art is gorgeous and the aesthetic consideration given to each card gently sprinkles everything you do with evocative imagery. It’s also interestingly diverse in the architecture and environment of the buildings and wonders – your civilization looks very windswept and interesting as you build it, and I often find myself idly enjoying the little artistic touches arrayed in front of me.

I’m also a big fan of the way in which it handles the initial card drafting of wonders, and the random setup of the game. You’re never quite sure when you’ll encounter particular cards, or even if they’re in play. Even experienced players may find themselves having to improvise in response to what the age offers, and how the flipping of face-down cards progresses. As you see the military, scientific or production situation slipping away from you, it creates an excellent sense of tension and an incentive to be creative in your approach to the game.

As usual, there are a few downsides to it. For all its randomness in setup and drafting, there isn’t a huge amount of variety in the box. Once you’ve played it a few times you’ve seen pretty much everything the game is going to offer you. You don’t know what it’s going to have in store for you in any given game, but you’ll know everything that is on the menu. And for all the dynamic possibility implied by the multiple different winning states, you need to play very badly, or have terrible luck, for them to be a real possibility. I did lose to a military conquest once, but I know exactly what I did wrong to let it happen. It’s unlikely to occur again, which means that for more experienced players those victories are more or less theoretical. You can easily prevent science victories with the tiniest bit of judicious forethought. Both systems offer value that isn’t linked to the victory itself of course, but it seems more could have been done to offer genuinely expressive paths of variable play.

Success in the end is as much down to randomness as it is to your own mastery of the game systems. I’m not a great fan of luck in games if It can consistently create the playing situations that allow a poor player to defeat a skilled player. I’m fine with it being the decider in a close game. I’m less fine with it deciding essentially the course of play for an entire session. 7 Wonders: Duel veers uncomfortably close to that line. The way in which cards are revealed is exciting and tense, but it does mean you can find yourself completely blocked out of viable play through no fault of your own. I mentioned above the game where Mrs Meeple had four wood producing cards, and the cheap wood trading cards. I could compensate to a degree, but so much of my game became about getting around that fundamental deficiency in my empire that I couldn’t meaningfully execute an effective strategy for victory. I spent my game fighting fires that I had no hand in starting.

Don’t let this dissuade you from picking up the game though – it is absolutely great. It’s quick to play, offers deep and involved decision making, and packs an awful lot of experience into its svelte duration. It’s not of the highest tier of excellence for me – not yet – but I’m certainly eyeing up the release date of the expansion with considerable interest. 7 Wonders: Duel is a game I’m sure that will get even better with a little more variety.